Staying Human In The Age of AI

A Chief Data Officer's Perspective On The Reshaping of Government Leadership

(12 min Read Time)

Like many people, I don’t know exactly what AI means for our future. Some parts of it excite me and others raise concerns. I’m optimistic about what these tools can unlock, and I’m also paying close attention to what we might lose along the way.

To help me think through it all, I reached out to a former colleague and friend, Oliver Wise, who currently serves as Chief Data Officer at the U.S. Department of Commerce. This piece reflects on our conversation and explores what AI is making possible in government, as well as what we need to protect.

When I asked Oliver how artificial intelligence is changing government, he didn’t start with tools or tactics. He started with people.

He has spent the last two decades thinking about performance, analytics, and the culture of public institutions. From his early work in the City of New Orleans to his current federal leadership role, he’s watched a quiet shift unfold. AI isn’t just making tasks faster, it’s altering the way people relate to their work, to each other, and to the decisions they make every day.

👋 Hey, it’s Jess. Welcome to my weekly newsletter, Thought(ful) Leaders, where I share practical tools and frameworks, share research, and interview thoughtful leaders on the future of work.

⛑️ Work with me for 1:1 executive coaching or book a workshop for your team.

If you’re not a subscriber yet, catch up on my latest articles from last month:

How Modern Government Teams Are Redesigning the Way Work Gets Done

What Most Teams Get Wrong About High Performance (and how to fix it)

Subscribe to get access to these posts, and all future posts.

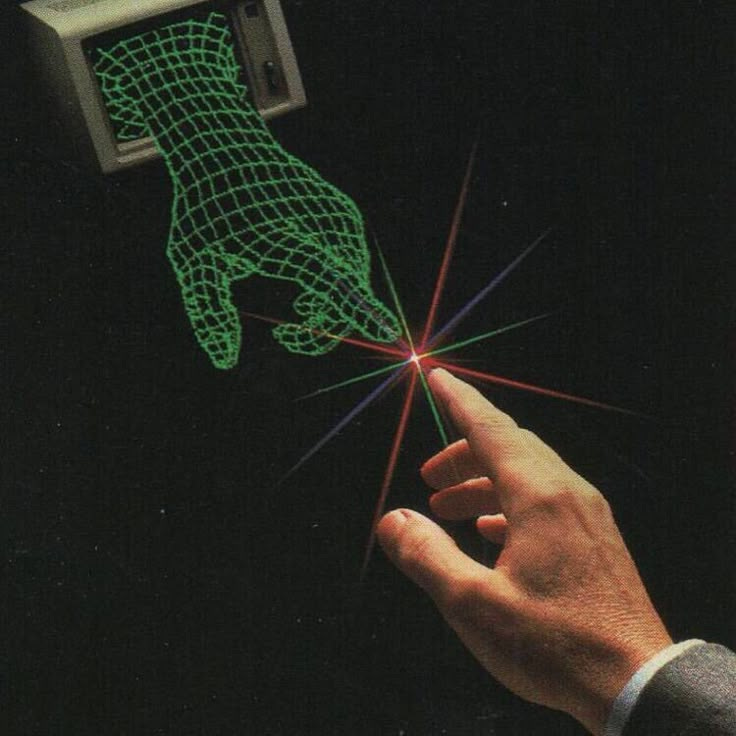

As AI becomes more accessible, knowledge work in government is evolving. Staff can now analyze information, generate ideas, and draft content in ways that once required teams of experts. This democratization of data can spark creativity and speed, but it also carries risks. When everything becomes easier to produce, the need for thoughtful judgment, ethical discernment, and meaningful communication becomes more important.

AI adoption is rising, with 75% of enterprises expected to operationalize AI by 2024 (Gartner).

A 68% skillset gap in AI talent - leading companies to prioritize upskilling on AI more than any other skill set (Deloitte).

AI is projected to create 97 million new jobs by 2025 but displace 85 million (World Economic Forum).

This is not only a moment of technical transformation, it’s a cultural one. Leaders must be ready to guide their teams through new ways of working while strengthening the human capabilities that make public service effective and trusted. That means creating space for shared learning, helping teams navigate uncertainty, and investing in core human skills that will be more needed than ever.

Here is what currently makes me optimistic and cautious about AI.

What Gives Me Optimism

From “Hot Seat” To Creative Problem Solving

Fifteen years ago, performance culture in government was centered on accountability. Tools like CompStat and CitiStat positioned executives in the “hot seat,” with rooms filled with dashboards and tough questions.

“There was this quasi-military culture,” Oliver recalled. “The theory of change was simple: if only people were held more accountable, better services would follow.”

But that model plateaued.

“We saw quick wins at first,” he said, “but the growth didn’t continue. Over time, it became clear that we needed more than vertical accountability. We needed horizontal accountability. Teams working together, looking out for each other, and staying focused on shared outcomes.”

And he’s right, performance meetings improved when they moved out of the spotlight and into closed-door collaboration. “You take out the performative element,” he said. “People can be real. You can focus on solving problems together instead of defending turf.”

This cultural evolution, from command-and-control to shared learning, set the stage for a new kind of performance: one where data isn't just reviewed, but used as a tool to collaborate and to think differently.

Here’s how each part of that model becomes more dynamic with AI.

Setting Goals: AI can analyze speeches, memos, and community input to surface themes and help set measurable, aligned goals. “That’s really the executive’s job, but AI can assist in turning big ideas into achievable, trackable goals.”

Tracking Performance: With AI automating data collection and interpretation, agencies can monitor progress in near real time, removing bottlenecks that previously required large analyst teams.

Getting Results: "This is where the magic happens," He said. "Creative problem-solving happens in the meetings. That’s where front-line staff bring their insight, and AI can help them brainstorm new approaches based on past patterns and emerging data."

This shift enables a transition from top-down reporting to a culture of horizontal accountability, one that emphasizes peer learning, shared ownership, and collaborative experimentation.

Oliver is especially encouraged by the work of local governments.

“They’re nimble. They don’t need to wait for a national policy. They can pilot, iterate, and start solving problems in new ways right now.”

Simplifying Bureaucracy with Workflow Automation

GenAI is also beginning to transform how governments operate, offering tools that can enhance efficiency, streamline processes, and improve decision-making. A notable example is San Francisco's initiative to modernize its municipal code.

San Francisco City Attorney David Chiu, in collaboration with Stanford University's Regulation, Evaluation, and Governance Lab, is leveraging AI to identify and eliminate outdated and redundant sections of the city's legal code.

The city's municipal code is extensive. It’s comparable in length to the entire U.S. federal rulebook, equating to approximately 75 volumes of "Moby Dick." Manually reviewing such a vast amount of text would be an insurmountable task for legal teams.

This case illustrates how AI can assist in decluttering bureaucratic processes, allowing government employees to redirect their efforts toward more impactful work.

However, it also underscores the importance of thoughtful implementation to ensure that the use of AI aligns with the goal of enhancing, rather than diminishing, human judgment and public service.

By employing AI, the team efficiently analyzed the code to pinpoint obsolete reporting requirements, such as mandates for reports on non-existent fixed newspaper racks. This effort led to a proposal to eliminate 140 out of nearly 500 reporting requirements, thereby freeing up staff time to focus on pressing issues (Politico. 2025).

“This isn’t just a San Francisco problem,” Chiu said, referencing a report that described the millions of pages produced by Congress every year as a black hole. “We need to be delivering results and services, not just churning out more reports,” he said. “Particularly in this era of budget scarcity we need to get up staff time to focus on the truly pressing issues of the day.”

Similar workflow automation is being used by the FDA. They recently launched ‘Elsa,’ an AI assistant that automates parts of the scientific review process to summarize adverse events and draf protocols. Wider adoption of these AI-powered workflows, from routing procurement requests to triaging citizen inquiries allows public servants to focus on more meaningful work.

Data For Everybody

One of the things Oliver is leading at the federal level is making public data like weather and climate data at noaa and economic and demographic data at census more accessible.

“We spent years making data open,” he said, “but we didn’t always make it usable. Most people aren’t going to download CSVs and build Tableau dashboards.”

He believes that LLMs (large language models) offer a major unlock.

“If we can publish our data in more AI-friendly formats, then anyone (residents, community groups, policy staff) can interact with it using natural language.”

For example, some cities now have on‑demand virtual assistants on their websites to guide residents through services. Everything from permit applications to voter registration is now commonly supported by chatbots. By publishing data in formats LLMs can parse more effectively, governments make it easy for non‑technical users to ask questions naturally and get clear, context‑accurate responses.

To support this, Commerce has released new guidelines for publishing public data in ways that are LLM-ready. Agencies like NOAA, the Census Bureau, and BEA are piloting these practices now, with support from NSF to modernize statistical data infrastructure. As Oliver points out,

“It could be a sea change in how the public engages with government data.”

Where I’m Cautious

Beware of Intellectual Atrophy

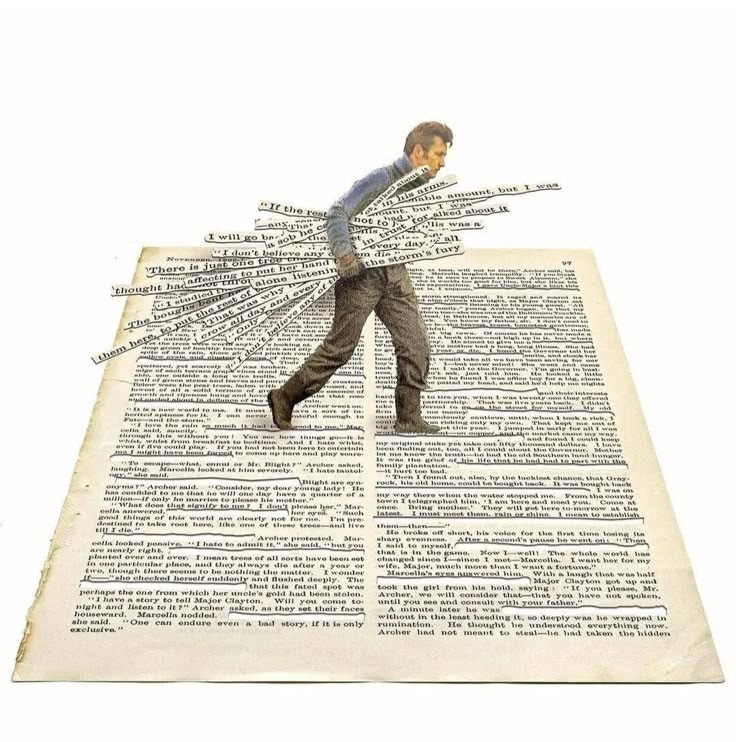

AI invites us to produce more, faster. But speed is not the same as clarity. Volume is not the same as insight. When we focus only on getting something generated, we lose the value of the creative process itself.

There is immense value in the struggle to make meaning, the time spent refining what we want to say, the effort it takes to really understand a problem.

For all its power, AI risks creating a world where we optimize everything except our own personal and intellectual growth.

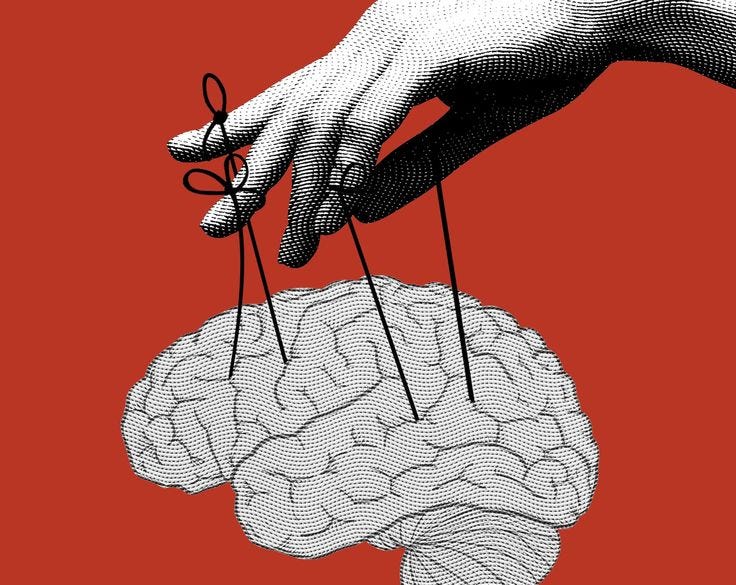

Sol Rashidi, former Chief Data and AI officer at several Fortune 100 companies warns us that we should be less afraid of losing jobs and more afraid of losing our critical thinking skills.

“Human cognitive abilities, such as critical thinking, common sense, intuition, and experience, require intention, focus, and attention span, all traits that are diminishing as we rely more on digital devices and AI tools.

The increasing accessibility of AI solutions is leading to an over-reliance on technology, diminishing our capacity for independent and critical thought.”

We get smarter, more creative, and better at pattern recognition when we go through the process ourselves. When things go wrong and we have to struggle through it, we become better leaders.

Don’t Let AI Flatten Your Voice

When every memo, email, or document is written by AI, you can tell. It feels cold. People disconnect.

In a recent piece titled The Great Flavorless Web, Mark Headd, former Chief Data Officer for the City of Philadelphia, warns about what we lose when we focus too narrowly on output in our use of AI tools.

He writes:

“A lot of what LLMs generate is just empty calories. Content that says nothing, means nothing, is often inaccurate, and exists just to fill the page. The way people use these tools doesn’t tend to produce anything that’s really ‘creative.’ It doesn’t invite deep insight. The goal is speed, volume, and coverage, not originality.”

This critique echoes a growing concern in government and beyond: as generative AI becomes more prevalent, we risk prioritizing efficiency over meaning, and convenience over creativity.

“If everything starts sounding like the same vaguely helpful listicle or generic blog post, we might forget how distinctive, human voices make us feel.”

What’s core to leadership is the ability to communicate with authentic emotional resonance and move people. Those qualities require presence, reflection, and the courage to say something real. AI can be a useful collaborator, but it cannot replace the deeply human skill of knowing what matters and saying it well.

This is why we must resist the temptation to treat speed and volume as the only measures of success. The tools may get better, but if we’re not careful, our voices will get flatter. Our leadership will become less personal. And our organizations will drift away from what makes them worth believing in.

The real opportunity with AI is not to do more faster. It is to free up space for deeper, more original thinking. It is to ensure that the work we do and the way we lead still reflects our humanity.

Strengthen Skills That Can’t Be Automated

As technology handles more of the analysis and content generation, the most important skills for public servants aren’t technical, they’re human. As the end product becomes easier to produce, it’s the human skills that need our investment and attention.

So what should leaders focus on?

Curiosity & Problem Framing

The best leaders resist the urge to jump to solutions. Instead, they get deeply curious about the problem and explore what they don’t know. As Oliver Wise put it, “Let ideas come from anywhere.” Leaders should stop pitching fully formed solutions and instead get better at “pitching the problem.”

Instead of asking, “How do we build a better application?” a curious leader might ask, “The data is showing us that 39% of applicants aren’t getting past the 4th step in our application process. Why might so many residents be dropping off halfway through? What else is happening in their experience?” That shift invites broader, more innovative thinking from the team.

Listening & Pattern Recognition

Listening well isn’t just about hearing what’s said, it's about noticing what’s repeated, what’s missing, and what it points to. Peter Senge, in The Fifth Discipline, calls this the foundation of systems thinking, the ability to recognize patterns, not just isolated events. Listening in this way helps leaders connect feedback loops across teams, spot trends early, and anticipate unintended consequences.

Try not to get stuck reacting to isolated complaints or incidents. First, ask yourself, Is this part of a larger pattern? Has something like this happened before?

Feedback & Productive Conflict

Feedback and conflict are two sides of the same coin. When teams can give and receive feedback with care, disagreement becomes a creative force without the hurt feelings. It’s not about preventing tension, but using constructively to sharpen ideas and strengthen the team.

The real red flag is when those around you stop offering feedback or openly sharing what’s going on. If people believe they will be punished for speaking up, you need to improve the psychological safety on your team. When tensions rise, ask: “Can we zoom out to clarify what we’re solving for?” or “What’s the core assumption we might be seeing differently?”

Empathy in Decision-Making

Empathy isn’t a soft skill, it’s a strategic one. It helps leaders understand the human consequences of their decisions and keeps systems accountable to the people they serve. I recently spoke with a policymaker who recounted his visit to a SNAP office to see firsthand how many hours it takes to complete an application. He applied, waited endlessly, and most importantly walked away feeling deeply dehumanized by the process. He understood the lived experience of the person on the other end of a policy he was working to reform. Further curiosity and investigation pointed to a reporting requirement that was creating paperwork bottlenecks in ballooning wait times. That insight prompted him to focus on reducing the reporting requirements, processing complexity, and advocate urgently for faster turnaround times.

Peer Accountability

Accountability isn’t just about reporting up the chain. Some of the highest-performing teams build horizontal accountability, where peers feel responsible for helping each other succeed.

Research from The Five Behaviors of a Cohesive Team shows that peer-to-peer accountability is a key differentiator of high-trust teams. When colleagues hold each other accountable, teams perform better and reduce reliance on top-down management. For example, a transit agency’s customer experience managers began holding weekly “learning sprints.” Each member reviewed each other's project plans and shared feedback. That peer review process reduced rework, built mutual trust and learning, and improved project velocity.

Embracing Technology and Leaning Into Humanity

AI is more than a tool. It reflects our intentions, values, and assumptions. It can help us work faster, but it can also widen gaps if used without care. What we build and how we lead with it will depend on the questions we ask and the choices we make.

In public service, those choices carry weight. The systems we build shape daily life, community trust, and future opportunity. AI should not be treated as just another strategy for efficiency. It requires a leadership mindset grounded in a pursuit for clarity, optimistic challenge, and deep care.

The best leaders do not chase every new tool. They create the conditions for thoughtful work. They invest in learning. They listen deeply and surface voices that might otherwise be missed. They stay with hard problems and draw on empathy and imagination to solve them.

We can build systems that reflect both our shared values and the complexity of the world we serve. We can use technology to amplify what makes our institutions humane, not just what makes them fast.

As the machines evolve, our responsibility is to remain present, reflective, and real. We need to stay human.

Thanks for reading.

🧭 Need support navigating this shift?

Book a free strategy call with me. We’ll walk through what’s working, what’s not, and where to begin. You can work with me for 1:1 executive coaching or bring me in to lead a workshop with your team.

📣 Enjoying Thought(ful) Leaders?

The best way to support this newsletter is to share it. Forward a post to a friend or colleague, or invite someone to subscribe. Word-of-mouth really matters.

💌 Got something to say?

Writing can feel like a one-way street. If you have thoughts, questions, or a perspective you want to add to the conversation, I’d love to hear from you. Reach me at jessica@jessicalynnmacleod.com.

Thanks for being here. More soon.

About Oliver Wise

Oliver Wise is Chief Data Officer at the Department of Commerce. In this position, Wise is responsible for leading the Commerce Department’s data strategy, advancing capacity for evidence-based decision-making by implementing the Evidence Act and aligning and scaling the department’s data resources to better meet the needs of users.

Wise was the founding director of the City of New Orleans Office of Performance and Accountability, the city’s first data analytics and performance management team. This work was recognized with awards from the American Society of Public Administration, International City/County Managers Association, Bloomberg Philanthropies, and Harvard University. In 2015, Wise was named to Government Technology’s “Top 25 Doers, Dreamers, and Drivers” list. In the private sector, Wise served in product management and strategic roles at Tyler Technologies and Socrata.

Earlier in his career, Wise was a policy analyst for the RAND Corporation and the Citizens Budget Commission of New York City. He is also a co-founder of the Santorini-based Atlantis Books. He holds an MPA from New York University’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, a bachelor’s degree from Tufts University, and is most proud of his incredible family.