If You Want to Understand Your Culture, Watch How the Work Gets Done

A conversation with Emily Barlow on why operations are never neutral and how to design them to work for your team

(10min Read)

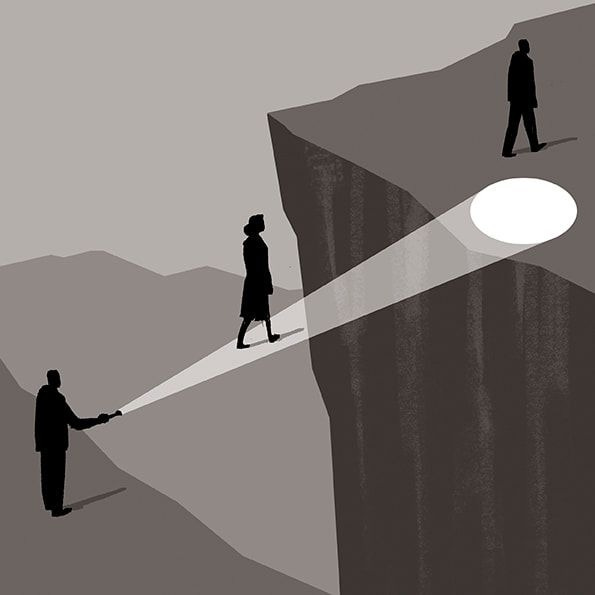

Most leaders care deeply about results. They focus on goals, motivation, talent, and collaboration. But far too often, they overlook something just as critical: the operational systems that make all of that possible. When teams experience friction, duplicated work, or slow momentum, the cause is frequently a lack of clarity about how to work together, not a lack of ambition or skill.

I’ve always been drawn to operations and process improvement, not because I love tools or templates, but because of what great ops unlocks. When someone is frustrated, overwhelmed, or burning out, improving how they work can feel like giving them oxygen. It frees up energy, restores momentum, and makes room for the bigger work that really matters.

I sat down with my former colleague and personally appointed operations expert Emily Barlow to talk about how to work well.

As Emily puts it, "If your team is spending all its energy figuring out how to get work done, they are not doing the work."

👋 Hey, it’s Jess. Welcome to my weekly newsletter, Thought(ful) Leaders, where I share practical tools and frameworks, share research, and interview thoughtful leaders on the future of work.

⛑️ Work with me for 1:1 executive coaching or book a workshop for your team.

If you’re not a subscriber yet, catch up on my latest articles from last month:

How Modern Government Teams Are Redesigning the Way Work Gets Done

What Most Teams Get Wrong About High Performance (and how to fix it)

Subscribe to get access to these posts, and all future posts.

This conversation explores the often invisible infrastructure that shapes how work happens. We go beyond the basics of documentation and tooling to examine how operational design reinforces trust, performance, and psychological safety. We also break down practical techniques leaders can use to observe friction, improve clarity, and guide behavior, especially in teams that are moving fast or working across functions.

Emily brings deep experience from her time at Apple and the U.S. Digital Response where urgency, scale, and complexity intersected. Her insights are particularly valuable for leaders who want to make better use of their team's energy and attention, and who understand that systems are not separate from culture. They are culture, made tangible.

Operational Misalignment Is a Design Problem

Many leaders assume that when a team is struggling to execute, the solution lies in better motivation or better tools. But often, the problem is upstream. The team does not have a shared understanding of what they are accountable for or how their work connects to others. Tools and templates are introduced in an attempt to bring order, but they do not resolve the underlying ambiguity.

Emily explained, "Tool issues are often symptomatic of something going on higher up in the stack. If we're all aligned on what our priorities are and what we are here to do, the tool piece is pretty easy to fix."

She shared a moment from a recent project where people were unsure about how to adjust an outdated rule. "I said, let's go up a few levels. Why did we make this rule in the first place? What was the original goal? Once we were aligned on that, the options became clearer."

This approach highlights a key principle: if a team is having tool problems, there is usually a higher-level disagreement about priorities or purpose that needs to be resolved first.

How to reframe:

Step back from tool debates and ask, "What was the original goal this process was trying to serve?"

Notice where confusion about ownership, decision rights, or priorities is showing up as tactical disorganization.

Align on purpose before aligning on workflows.

Team Charters and Shared Definitions Create Structural Clarity

When Emily joined U.S. Digital Response, one of her first actions was to lead teams through a team chartering exercise. She asked each group to write down what they were responsible for, how they contributed to the broader mission, and how they interacted with other teams. This was not a theoretical exercise. It quickly revealed areas of overlap, duplication, and misaligned expectations.

“You can say, write down what you think you're supposed to be doing here. Then compare notes. That often tells you everything you need to know."

Charters are a practical tool to clarify roles, boundaries, and purpose. They give people language to talk about their work and provide a reference point for decision-making. In environments where work evolves rapidly or team membership shifts frequently, charters create a stabilizing layer of shared understanding.

What to include in a team charter:

The mission of the team and how it supports the organization's larger goals

Key responsibilities and areas of ownership

What success looks like

Interfaces with other teams and decision boundaries

Observe How Work Really Happens

One of Emily's most important lessons is the value of direct observation. Leaders often rely on reports, retros, or performance reviews to understand what is happening. But the clearest insights come from watching people try to do their jobs.

She describes this as a form of operational ethnography. Sit next to someone (or screen share) and ask them to walk you through a typical task.

Rather than jumping straight to solutions, Emily recommends watching people work.

"Sit down and shadow someone. Ask them to show you what they do. Have them narrate it: first I go here, then I have to find this tab, then I ask someone for help. That tells you where the friction is."

These moments are not just inefficiencies. They are indicators of where systems are misaligned with reality.

Signs to look for:

People toggling between multiple tabs or tools to complete a simple task

Tasks that rely heavily on tribal knowledge or individual memory

Repetitive questions that suggest information is not easy to find

Good Systems Nudge the Right Behavior

Once a team is clear on its purpose, the next challenge is shaping behavior in consistent and effective ways.

Emily emphasizes that people do not resist processes because they are lazy or difficult. They resist it because it often adds complexity without delivering value. The goal of good operations is not to impose structure. It is to make it easy to do the right thing.

She described how she redesigned the volunteer request system at USDR, which operated as a dual-sided marketplace—matching volunteers with government agencies who submitted requests for support. “Everyone was in Slack, but we needed them to use Airtable. The change made requests easier to track and manage—but it wasn’t about improving the experience for requesters. We knew people were motivated to make requests, so we used that moment to introduce a system that helped the org run better,” she said.

To ease the transition, her team replicated what people liked about the old workflow, especially the interactive back-and-forth with the volunteers team in Slack. “That conversation felt important to people, so we preserved it while shifting the core request flow,” she explained.

Her focus was always on reducing friction. “I sent people the exact record link, not just to the general tool. If they had to search for the right place, they wouldn’t do it. You have to make it easy to do the right thing.”

Design principles:

Meet people where they already are and gradually embed new behaviors into existing workflows

Use automations and links to reduce the cognitive load of switching contexts or hunting for the right form

Align systems with the outcomes people care about

Simplify the Rules of the Road

Knowing what the team is accountable for is not enough. People also need clarity on how work gets done. This includes norms around documentation, tool use, decision-making, and communication. Without this, even the most well-intentioned teams end up duplicating effort, overlooking key steps, or working at cross-purposes.

Emily calls this "ops choreography": the invisible rhythm that underlies effective teams.

She explained, "It’s the rhythm of the organization. When we say: here’s how we request something, here’s how decisions get made, here’s where documents go—it saves everyone from wasting time."

What to define:

Tool conventions (for example, tasks in Trello, notes in Notion)

Communication expectations (for example, when to use Slack versus meetings)

Decision-making processes and who owns what

Rethink Documentation as a Living Asset

Documentation is often treated as an administrative task or a compliance exercise. Emily is a documentation skeptic. "People don’t read long docs. And if they hit one outdated thing, they lose faith in the rest. Then even the good parts don’t get used."

Documentation should be alive. It should be useful. And it should be close to the work.

Her approach favors embedded guidance, short videos, and context-specific help. A short video that walks through a workflow may be more effective than a 10-page PDF. The goal is not completeness. It is usability.

Sustainable documentation practices:

Keep documentation short, current, and targeted to common questions

Assign ownership for updates and review

Make documentation discoverable in the places people already work

Visibility Builds Trust and Momentum

One of the most powerful cultural signals in a team is where work happens. At USDR, the default was to work in public channels, shared folders, and open tools. This created not just efficiency, but a sense of shared ownership. When people can see what others are working on, they can offer help, avoid duplication, and build on each other’s progress.

Emily contrasts this with environments where work lives in DMs or private folders. These systems create single points of failure and increase coordination costs. More importantly, they erode the connective tissue that makes a team feel like a team.

Still, we both acknowledged that many organizations struggle to build this habit.

"Sometimes leaders think the problem is just that people are ignoring the policy. But you have to ask: why are people choosing closed channels or DMs? Why are people hiding?”

There could be any number of reasons. People may be trying to avoid unsolicited feedback, fear criticism of their work or questions, might be having trouble navigating sensitive topics, or responding to incentive structures that reward individual visibility over collective progress.

"If you want people to work in the open, you need to make sure it feels safe and worth it to do so."

Norms to reinforce:

Default to open channels and collaborative documents

Use shared boards or dashboards to track progress

Recognize and reinforce visibility as a leadership behavior

Change Management Is Part of Operational Design

Building better systems is not enough. You also need people to use them.

"The tools don’t work unless people use them," Emily said. "And people won’t use them unless the new way is easier than the old way."

She emphasized starting with a real pain point. "Don’t invent a process for its own sake. Find the thing people are struggling with, solve that, and then slowly build around it."

She recommends starting with a clear pain point, designing a simple solution, and socializing it through use. Sometimes that includes gently closing off back doors. At USDR, once the Airtable process was live, the team stopped responding to Slack requests. This was not punitive. It was about signaling that the new process was real, supported, and required.

Steps to support change:

Identify the high-leverage behavior you want to shift

Make the new path easier than the old one

Reinforce through visibility, reminders, and peer modeling

Operations Reflects What You Value

Leaders often separate operations from strategy, culture, or leadership. But the truth is, your operational systems are how your values show up in practice. If you say you value collaboration, but work lives in silos, the system sends a different message. If you say you care about impact, but teams spend hours chasing down information, the system gets in the way.

Emily Barlow reminds us that operational clarity is not about control. It is about respect.

As she puts it:

"When you give people clarity, you give them energy back.

You let them focus on the work that matters."

If you want a better team experience, do not just ask people to work harder. Design a better system for them to succeed.

You Don’t Have To Do This Alone

If you need some support, book a free strategy call with me and we’ll walk through what’s working, what’s not, and where to begin. You can work with me for 1:1 executive coaching or book a workshop for your team.

If you want to support Thought(ful) Leaders, the best way is simple: share this newsletter. Forward the posts you love to a friend or colleague, or encourage someone to subscribe. That kind of word-of-mouth makes all the difference!

If you have topics you’d love for me to cover in future newsletters, send me a note: jessica@jessicalynnmacleod.com

Thanks for being here. More soon.

About Emily Barlow

Emily is a former founding staff member of U.S. Digital Response and a former program and supply chain manager at Apple.

She loves building and running systems that help teams thrive, especially those working in her undergraduate field of Materials Science. She’s currently exploring opportunities to apply her operations expertise to the climate sector—particularly in energy storage solutions that can accelerate the transition to clean energy and electrify the world. Outside of work, you’ll find her taking photos of her Samoyed, trying new restaurants in San Francisco, winning at bar trivia, or planning a ski trip.